Keith M Johnston talks about the origins of the film trailer.

While preparing for a recent talk on trailers at the University of Nottingham, I revisited some old research materials on the early years of the trailer including industry ‘talk’ about the trailer, its value, and its use by exhibitors. After the talk, I received a few questions about trailer history, and those initial years of trailer formation / development. All of which led me to thinking about when the trailer would celebrate its centenary.

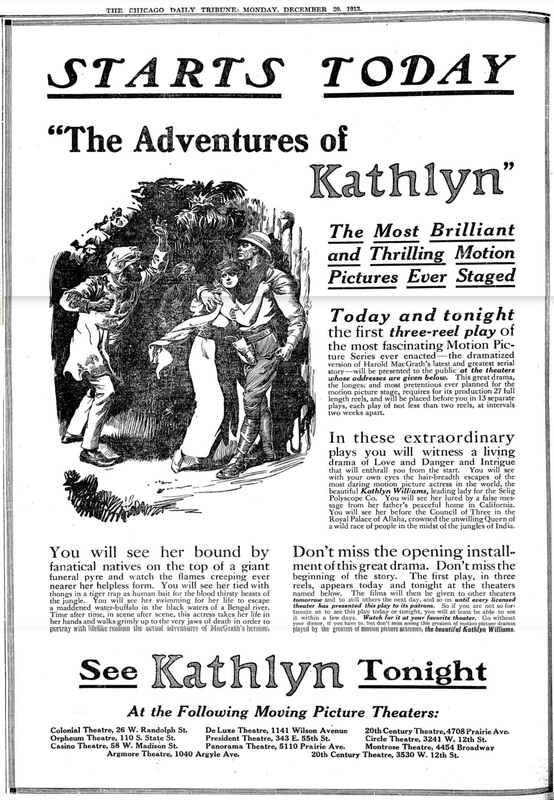

Keith J. Hamel’s fascinating exploration of advertising practices of the early 1910s points to various claims that the term ’trailer’ is in circulation as early as 1911. He cites a discussion in The New York Dramatic Mirror that refers to a trailer as a “strip of blank film to attach to the end of a reel”, before considering (and dismissing) propaganda, ‘behind-the-scenes’ films and commercial films of the time period as contenders for the first trailers. (Hamel 2012: 269-70) My Watching the Trailer colleague Fred Greene has also noted the existence of ‘proto-trailers’ such as the addition of a slide to the end of a serial such as The Adventures of Kathleen (1913) prompting audiences to ‘See next week’s thrilling episode.’ (Greene 2013)

While preparing for a recent talk on trailers at the University of Nottingham, I revisited some old research materials on the early years of the trailer including industry ‘talk’ about the trailer, its value, and its use by exhibitors. After the talk, I received a few questions about trailer history, and those initial years of trailer formation / development. All of which led me to thinking about when the trailer would celebrate its centenary.

Keith J. Hamel’s fascinating exploration of advertising practices of the early 1910s points to various claims that the term ’trailer’ is in circulation as early as 1911. He cites a discussion in The New York Dramatic Mirror that refers to a trailer as a “strip of blank film to attach to the end of a reel”, before considering (and dismissing) propaganda, ‘behind-the-scenes’ films and commercial films of the time period as contenders for the first trailers. (Hamel 2012: 269-70) My Watching the Trailer colleague Fred Greene has also noted the existence of ‘proto-trailers’ such as the addition of a slide to the end of a serial such as The Adventures of Kathleen (1913) prompting audiences to ‘See next week’s thrilling episode.’ (Greene 2013)

Chicago Tribune December 29, 1913

Hamel and Greene both discuss ‘a forty-five second strip of film containing three shots’ that promoted the serial The Red Circle (1915). There is some disagreement around their description of that strip of film: Hamel identifies a title slide, then two similar live action images of a hand on which a circle appears (through the use of a dissolve) (2012: 271) while Greene notes the same title slide, but adds a jewelled ring floating in space and the face of star Ruth Roland.

Red Circle (courtesy Wikipedia/ SabuCat Trailers)

For me, The Red Circle example sits at the intersection of the exhibitor’s use of “series slides” and the creation of “an advance strip of film”, a term used to describe Famous Players’ short film advertising The Quest of Life in 1916. The “series slide” was a set of static glass slides that were used with a projector in a cinema between other parts of the programme. Epes Winthrop Sargent, an ex-Vitagraph publicity man who wrote a weekly column on advertising for The Moving Picture World, claimed that exhibitors that tended to use one simple slide (‘The Smugglers – A Big Three Reel Lupex – Shown Here Saturday’) would be better served by introducing individual elements and narrative across a series of slides. His Smugglers example would then look like:

- $10, 000, 000 in diamonds

- And not a cent of duty paid, but

- Inspector Davis (played by Cecil Coyley)

- Ran the swindlers down.

- The Smugglers – here Thursday

- A Lupex three-part thriller. (Sargent Picture Theatre Advertising 1915, p.55)

Series slides could easily add in images – narrative hints or star shots – as well as text, and seem to resemble the broad description of The Red Circle strip of film, with its focus on a developing narrative.

The advance strip of film for The Quest of Life, however, contained ‘one of the famous dances of these Terpischorean stars [dancers Maurice and Florence Walton]’ and was developed ‘in the belief that the screen itself is the best way to advertise motion pictures.’ (Moving Picture World, 30 September 1916, 2094) Here, we have title cards, but also a specific piece of film that seems to act as a free sample of what audiences will see if they watch the feature. And that might be an important point – this advance strip of film was promoting a feature, not the next episode of a serial – which leads me to wonder if we should consider feature promotion as one of the marks of trailer development in this period? To me, while The Quest of Life isn’t quite the trailer format that would dominate in later years, Bioscope’s description of it as giving ‘the public a foretaste of what the photoplay will provide’ does feel like a stronger statement of the potential of the trailer than The Red Circle.

But, of course, The Quest of Life advance film was never (apparently) referred to as a trailer, and it lacks the montage of excerpted footage that would become a convention through the 1920s and beyond. By July 1917, however, only 10 months after The Quest of Life advance film was released, The Moving Picture World defined the trailer as ‘flashing a few scenes to stimulate curiosity in a coming production’ and that the promotional format had ‘come into use extensively of late’. (MPW 28 July 1917, p. 663)

While Hamel sees this as evidence to support The Red Circle, I think The Quest of Life has a stronger claim: not only is September 1916 more ‘of late’ than 1915, but I believe the link to feature promotion is key. Of course, the quest for the ‘first’ trailer is largely a fruitless task, given the shifting definitions in this period (and partial archiving practice for promotional materials more generally). What is clear from these existing sources is that by July 1917 the industry has accepted the term trailer, and given it a broader definition based around a montage of excerpted footage and title slides.

By 1919, The Exhibitors Herald and Motograph was claiming the trailer to be ‘an old idea’ while accepting its role was to provide ‘a short resume of the coming picture’ (3 August 1919, p35), and the trailer producer National Screen Service was being established in New York to get studios ‘out of the nickel and dime business of selling trailers and posters and stills to individual theatres’ (Lazarus quoted in Johnston 2009, 171). The trailer was an established part of the industry, and has not given up that position since.

So, what does that tell us about the trailer’s 100th birthday?

I would argue it is this year, and that we should be celebrating 100 years of this fascinating and complex coming attraction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed