In Anthony Trollope's minor novel about trade and advertising, The Struggles of Brown, Jones & Robinson (1862), three business partners express attitudes and notions about truth, representation and consumer expectation echoed in our own contemporary research among movie trailer audiences. In the sophistication, cynicism and naivete of the various protagonists’ remarks about marketing, you can read the same skepticism, confusion and plain ignorance regarding a mode of communication that is only more ubiquitous and compelling today

‘"But, George," said Mr. Brown, "I should like to have one of these bills [advertising notices] true, if only that one might show it as a sample when the people talk to one."

"True!" said Robinson, again. "You wish that it should be true! In the first place, did you ever see an advertisement that contained the truth? If it were as true as heaven, would any one believe it? Was it ever supposed that any man believed an advertisement? Sit down and write the truth, and see what it will be! The statement will show itself of such a nature that you will not dare to publish it. There is the paper, and there the pen. Take them, and see what you can make of it."

"I do think that somebody should be made to believe it," said Jones.

[Jones, the other partner, is vain, venal and dull-witted]

"You do!" and Robinson, as he spoke, turned angrily at the other. "Did you ever believe an advertisement?" Jones, in self-defence, protested that he never had. "And why should others be more simple than you? No man,—no woman believes them. They are not lies; for it is not intended that they should obtain credit. I should despise the man who attempted to base his advertisements on a system of facts, as I would the builder who lays his foundation upon the sand. The groundwork of advertising is romance. It is poetry in its very essence. Is Hamlet true?"

"I really do not know," said Mr. Brown.

"There is no man, to my thinking, so false," continued Robinson, "as he who in trade professes to be true. He deceives, or endeavours to do so. I do not. No one will believe that we have fifteen hundred dozen of Balbriggan." [A kind of stockings.]

"Nobody will," said Mr. Brown.

"But yet that statement will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist to our mill without any dishonesty on our part. Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive. Once understand that, and you will cease to ask for truth." Then he turned himself again to his work and finished his task without further interruption.’

{Emphases and interpolated notes are mine; Text courtesy of Project Gutenberg}

150 years ago, Trollope (and we presume, some of his audience) disdained the truth claims of advertising, recognizing their near irrelevance to the communicational activity afoot. At the same time, he acknowledges the power of their aesthetic and emotional appeals. But while the fictional Robinson is incipiently post-modern in his conception of marketing communications and wicked in his satire, contemporary audiences appear to have regressed relative to Victorian counterpart in their critical evaluation of advertising.

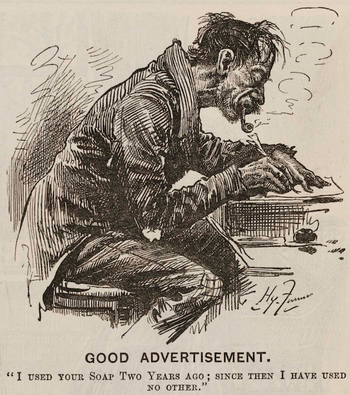

(Editors note: Below Harry Furniss' famous 'I used your soap' cartoon, an illustration of the cynicism surrounding 19th Century Ads - this somewhat ironically, became used by a soap company.)

‘"But, George," said Mr. Brown, "I should like to have one of these bills [advertising notices] true, if only that one might show it as a sample when the people talk to one."

"True!" said Robinson, again. "You wish that it should be true! In the first place, did you ever see an advertisement that contained the truth? If it were as true as heaven, would any one believe it? Was it ever supposed that any man believed an advertisement? Sit down and write the truth, and see what it will be! The statement will show itself of such a nature that you will not dare to publish it. There is the paper, and there the pen. Take them, and see what you can make of it."

"I do think that somebody should be made to believe it," said Jones.

[Jones, the other partner, is vain, venal and dull-witted]

"You do!" and Robinson, as he spoke, turned angrily at the other. "Did you ever believe an advertisement?" Jones, in self-defence, protested that he never had. "And why should others be more simple than you? No man,—no woman believes them. They are not lies; for it is not intended that they should obtain credit. I should despise the man who attempted to base his advertisements on a system of facts, as I would the builder who lays his foundation upon the sand. The groundwork of advertising is romance. It is poetry in its very essence. Is Hamlet true?"

"I really do not know," said Mr. Brown.

"There is no man, to my thinking, so false," continued Robinson, "as he who in trade professes to be true. He deceives, or endeavours to do so. I do not. No one will believe that we have fifteen hundred dozen of Balbriggan." [A kind of stockings.]

"Nobody will," said Mr. Brown.

"But yet that statement will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist to our mill without any dishonesty on our part. Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive. Once understand that, and you will cease to ask for truth." Then he turned himself again to his work and finished his task without further interruption.’

{Emphases and interpolated notes are mine; Text courtesy of Project Gutenberg}

150 years ago, Trollope (and we presume, some of his audience) disdained the truth claims of advertising, recognizing their near irrelevance to the communicational activity afoot. At the same time, he acknowledges the power of their aesthetic and emotional appeals. But while the fictional Robinson is incipiently post-modern in his conception of marketing communications and wicked in his satire, contemporary audiences appear to have regressed relative to Victorian counterpart in their critical evaluation of advertising.

(Editors note: Below Harry Furniss' famous 'I used your soap' cartoon, an illustration of the cynicism surrounding 19th Century Ads - this somewhat ironically, became used by a soap company.)

Like Robinson’s partner, Jones, contemporary trailer audiences (a significant portion thereof) express beliefs about and expectations for advertising incompatible with what they otherwise claim to know and understand about marketing language and its approximation to truth and accuracy. In our data set, respondents shared frustration with misleading trailers, which is a perfectly natural response to being misled, lied to and persuaded to spend money on a good, service or experience that is not as promised and described. Yet, elsewhere in the survey—often in the same comment-- many acknowledge that “of course, you can’t trust a trailer.” So what elicits trust in the siren call of the trailer when experience and functional knowledge teach suspicion and caution?

On the other side of the exchange, Trailer makers want to provide information to audiences that allows them to choose wisely. An unhappy and disappointed movie goer is a liability and sales dampener –just as a gratified and delighted movie goer is an asset and ambassador- and this was true even before the amplification of social media made everyone a widely published critic. But when the need to “open” a film meets audience gullibility, trailers that misrepresent will find audiences who resent.

For both parties to the encounter, it’s a case of knowing better and not knowing better. Historically and economically, this ambivalent relationship between movie marketers and their audiences is neither new nor especially dangerous—at least not yet. Still, as a cognitive problem or intellectual scandal, it’s a curious case.

Let me stipulate that our research confirms the received understanding of trailers as generally enjoyable and effective purveyors of persuasive appeals to targeted audiences regarding the movie-viewing experience in question. But it’s the squeaky wheel of audience disappointment and hostility toward the world’s favorite advertising that grabs attention and inspires my own interest.

Because the disappointment, disgust, frustration, anger, resentment or delight of audiences regarding a movie trailer implies that the feature film has also been consumed--or at least that the audience has learned from other sources what the film is actually like—the emotional intensity of the response is an index of engagement. Consequently, the gap between expectation and fulfillment may be thought to be predictive of the intensity of hostility or delight, resentment or approval, with which audiences respond to a given trailer.

When our first year survey data were released to the media, headlines trumpeted “disappointment” as the key finding (it was but one among others) as if it were news that audiences, viewers and readers disliked being lied to, misled or fooled. And yet, there is no crisis in the trailer industry; no boycott of trailers, and only frivolous litigation. The risk of disappointment is faced and surmounted regularly by movie audiences trailer after trailer, release after release. I’m inclined to think the challenge of “reading” a trailer, “parsing” it’s positioning for the truth of the feature, is itself part of the movie consuming experience, an entertainment all its own, insofar as one gambles with time, money and desire for pleasurable outcomes. Under this hypothesis, frustration or disgust is a predictable result of judging, guessing or hoping wrongly. Certainly it’s easier and more agreeable to blame the marketers than ones’ own faculty of prediction.

I return to Trollope for his insight into the understanding of advertising by the typical 1860’s consumer, for whom partner Jones is our proxy. Robinson insists and makes Jones agree that “no one” is fooled by the truth claims of advertising: “No man,—no woman believes them. They are not lies; for it is not intended that they should obtain credit.” And yet, advertising communications regularly and predictably motivate behavior and yield results: “…that statement will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist to our mill without any dishonesty on our part. Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive. Once understand that, and you will cease to ask for truth.”

Commercial stories and assertions appear to operate upon us much like fictional ones, eliciting emotional and cognitive responses. As Robinson appreciates, despite knowing better, audiences—then and now--can’t control ourselves. Advertising appeals to sensibility, which is code for non-logical processes. Indeed, Robinson bases his argument on aesthetic and rhetorical principles: “the groundwork of advertising is romance. It is poetry in its very essence.” Making the point more emphatically, he asks Jones, “Is Hamlet true?”

Certainly there are those—constituting a statistically significant percentage of audiences surveyed--who ignore the commercial imperative of trailers, neglecting to reckon with their function as advertising, their lack of accountability to literal or aesthetic truth. It is as if for some ticket buyers, marketing, journalism, promotion and news are no longer distinguishable or so totalizing as to prevent their imagining an alternative. Meanwhile, the “truth in advertising” meme—a cynical rule propagated by the Federal Trade Commission of the United State—has gained a purchase on the consumer mind, despite compelling evidence of its lax and halting enforcement.

In 1860, the skepticism assumed by Robinson and grudgingly acknowledged by Jones, seems more an expression of Trollope’s irony than an accurate characterization of the Victorian consuming public. Much of the book is devoted to accounts of Robinson’s mastery of advertising and promotion in as many media as were then available to him. And in each ingenious “campaign” that he writes and executes on behalf of the business, he finds credulous audiences for indifferent goods at unremarkable prices. Only occasionally, as with marketers, does he meet with consumer distrust.

If, as I think probable, audiences, trailer makers and media critics are speaking past each other because of a failure to agree on precise definitions and a reliance on sloppy metaphors, let me mention a conception that is as wrong as it is frequently deployed. Where I think the problem lies (and the “problem” may not be a problem for the box office, but rather a successful strategy of engagement) is in the mis-identification of trailers as a “free sample” of the film the audience is thinking of consuming. Unlike a bona fide sample, say a trial portion of cologne from the cosmetic counter or cube of cheese handed out at the grocery, a 2:00 trailer isn’t isotonic with the feature, like the cologne or cheese is with its larger bottle or wedge. No, a trailer is another kind of film, smaller, differently edited, telling a different story with different graphic design features, music and extra-diegetic text. While it might present shot sequences taken frame by frame from the feature, they have been slotted into a different structure, incorporated into another film altogether.

A trailer is a film about a film, a story about a film, an allegory even, rather than a sample, a bite, a sip. A trailer must inevitably fall short of representing a film given that its function is otherwise: to position a film, provide information about a film and advocate for its excellence. And then, its components and style of narrative articulation are very different. Audiences who know better and those who don’t nonetheless persist in demanding from trailers experiences and assurances they are unable to provide. And yet, to borrow the idiom of Trollope’s advertising avatar, Robinson, that presumption “will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist” to the mill “without any dishonesty” on the part of the respectable movie marketer. “Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive.” Trailermakers know this. Shouldn’t audiences?

On the other side of the exchange, Trailer makers want to provide information to audiences that allows them to choose wisely. An unhappy and disappointed movie goer is a liability and sales dampener –just as a gratified and delighted movie goer is an asset and ambassador- and this was true even before the amplification of social media made everyone a widely published critic. But when the need to “open” a film meets audience gullibility, trailers that misrepresent will find audiences who resent.

For both parties to the encounter, it’s a case of knowing better and not knowing better. Historically and economically, this ambivalent relationship between movie marketers and their audiences is neither new nor especially dangerous—at least not yet. Still, as a cognitive problem or intellectual scandal, it’s a curious case.

Let me stipulate that our research confirms the received understanding of trailers as generally enjoyable and effective purveyors of persuasive appeals to targeted audiences regarding the movie-viewing experience in question. But it’s the squeaky wheel of audience disappointment and hostility toward the world’s favorite advertising that grabs attention and inspires my own interest.

Because the disappointment, disgust, frustration, anger, resentment or delight of audiences regarding a movie trailer implies that the feature film has also been consumed--or at least that the audience has learned from other sources what the film is actually like—the emotional intensity of the response is an index of engagement. Consequently, the gap between expectation and fulfillment may be thought to be predictive of the intensity of hostility or delight, resentment or approval, with which audiences respond to a given trailer.

When our first year survey data were released to the media, headlines trumpeted “disappointment” as the key finding (it was but one among others) as if it were news that audiences, viewers and readers disliked being lied to, misled or fooled. And yet, there is no crisis in the trailer industry; no boycott of trailers, and only frivolous litigation. The risk of disappointment is faced and surmounted regularly by movie audiences trailer after trailer, release after release. I’m inclined to think the challenge of “reading” a trailer, “parsing” it’s positioning for the truth of the feature, is itself part of the movie consuming experience, an entertainment all its own, insofar as one gambles with time, money and desire for pleasurable outcomes. Under this hypothesis, frustration or disgust is a predictable result of judging, guessing or hoping wrongly. Certainly it’s easier and more agreeable to blame the marketers than ones’ own faculty of prediction.

I return to Trollope for his insight into the understanding of advertising by the typical 1860’s consumer, for whom partner Jones is our proxy. Robinson insists and makes Jones agree that “no one” is fooled by the truth claims of advertising: “No man,—no woman believes them. They are not lies; for it is not intended that they should obtain credit.” And yet, advertising communications regularly and predictably motivate behavior and yield results: “…that statement will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist to our mill without any dishonesty on our part. Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive. Once understand that, and you will cease to ask for truth.”

Commercial stories and assertions appear to operate upon us much like fictional ones, eliciting emotional and cognitive responses. As Robinson appreciates, despite knowing better, audiences—then and now--can’t control ourselves. Advertising appeals to sensibility, which is code for non-logical processes. Indeed, Robinson bases his argument on aesthetic and rhetorical principles: “the groundwork of advertising is romance. It is poetry in its very essence.” Making the point more emphatically, he asks Jones, “Is Hamlet true?”

Certainly there are those—constituting a statistically significant percentage of audiences surveyed--who ignore the commercial imperative of trailers, neglecting to reckon with their function as advertising, their lack of accountability to literal or aesthetic truth. It is as if for some ticket buyers, marketing, journalism, promotion and news are no longer distinguishable or so totalizing as to prevent their imagining an alternative. Meanwhile, the “truth in advertising” meme—a cynical rule propagated by the Federal Trade Commission of the United State—has gained a purchase on the consumer mind, despite compelling evidence of its lax and halting enforcement.

In 1860, the skepticism assumed by Robinson and grudgingly acknowledged by Jones, seems more an expression of Trollope’s irony than an accurate characterization of the Victorian consuming public. Much of the book is devoted to accounts of Robinson’s mastery of advertising and promotion in as many media as were then available to him. And in each ingenious “campaign” that he writes and executes on behalf of the business, he finds credulous audiences for indifferent goods at unremarkable prices. Only occasionally, as with marketers, does he meet with consumer distrust.

If, as I think probable, audiences, trailer makers and media critics are speaking past each other because of a failure to agree on precise definitions and a reliance on sloppy metaphors, let me mention a conception that is as wrong as it is frequently deployed. Where I think the problem lies (and the “problem” may not be a problem for the box office, but rather a successful strategy of engagement) is in the mis-identification of trailers as a “free sample” of the film the audience is thinking of consuming. Unlike a bona fide sample, say a trial portion of cologne from the cosmetic counter or cube of cheese handed out at the grocery, a 2:00 trailer isn’t isotonic with the feature, like the cologne or cheese is with its larger bottle or wedge. No, a trailer is another kind of film, smaller, differently edited, telling a different story with different graphic design features, music and extra-diegetic text. While it might present shot sequences taken frame by frame from the feature, they have been slotted into a different structure, incorporated into another film altogether.

A trailer is a film about a film, a story about a film, an allegory even, rather than a sample, a bite, a sip. A trailer must inevitably fall short of representing a film given that its function is otherwise: to position a film, provide information about a film and advocate for its excellence. And then, its components and style of narrative articulation are very different. Audiences who know better and those who don’t nonetheless persist in demanding from trailers experiences and assurances they are unable to provide. And yet, to borrow the idiom of Trollope’s advertising avatar, Robinson, that presumption “will have its effect. It will produce custom, and bring grist” to the mill “without any dishonesty” on the part of the respectable movie marketer. “Advertisements are profitable, not because they are believed, but because they are attractive.” Trailermakers know this. Shouldn’t audiences?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed