Back in March, the Watching the Trailer team (Fred Greene, Keith M. Johnston, and Ed Vollans) travelled to Montreal for the Society of Cinema & Media Studies (SCMS) annual conference. As well as meeting new and old friends in the trailer / promotional studies scene, we were there to present a series of (inter-related) papers on our ongoing audience research project.

Given we can’t share the physical presentations with you, here’s the next best thing: a series of blog posts that consider specific aspects of those papers. The first of these is Keith’s exploration of how some of the results of our audience research echo historical commentaries on the trailer from the film industry and general press… enjoy!

-------------------------------------------------------------

Given we can’t share the physical presentations with you, here’s the next best thing: a series of blog posts that consider specific aspects of those papers. The first of these is Keith’s exploration of how some of the results of our audience research echo historical commentaries on the trailer from the film industry and general press… enjoy!

-------------------------------------------------------------

In 1954, London’s Evening Standard published a cartoon of a man and woman outside a cinema. One of them (it appears to be the woman) says “It wasn’t as good as the trailer!” That cartoon was then used in an advertisement for British trailer company National Screen Service, as reproduced here.

In 2014, over 50 respondents to our first trailer audience survey made similar comments:

So, let’s look at some specific examples to show you what I’m talking about:

In 2014, over 50 respondents to our first trailer audience survey made similar comments:

- ‘The [Man of Steel] trailer was fantastic… [it] had a better story, better pacing, better use of music, and stronger emotions than the film did.’ (#143)

- ‘Trailers are often better than the film’ (#308)

- ‘The [Saving Mr Banks] trailer made me happy… [the film had an] overall lack of storytelling in comparison to the trailer’ (#179)

So, let’s look at some specific examples to show you what I’m talking about:

‘Trailers these days show a summary of the absolute entire damn plot.’ (#29)

Ryan Gibley has argued that while they were once ‘a sophisticated tease’, modern trailers are ‘annihilating the expectation of excitement, the bliss of ignorance’ (‘Trailer trash’ New Statesmen 13 March 2006, p.42) – while the language of our survey respondents might be softer, there is a partial comparison here: 47 making direct claims that the trailer revealed too much. However, contrary to Gibley’s other claim, there is little evidence from trailer history that points to any sort of Golden Age of trailer sophistication, or that trailers were ever coy about making such plot revelations.

85 years before Gibley’s article (5-9 years after the film trailer was first used in cinema advertising: the debate about what the first trailer was, or when it was released, is a story for a whole other blog) the tone of such industry talk was – initially – kinder. The U.S. Exhibitors’ Trade Review noted that ‘theatres appreciate the artistic and mechanical efficiency’ of the trailer, while a film producer ‘knows that the public is receiving a true and definite conception of what his pictures stand for”.’ (Nov 5 1921, p1597) The idea of a ‘true… conception’ seems far removed from the experience of at least some of our participants, and the wider online debate around trailers regularly returns to the idea of complaints or frustrations over the ‘spoiler’ text.

Positive talk about trailers did not last very long, however. In the early sound era, The New York Times’ Mordaunt Hall demanded trailers of ‘a more judicious fashion, with a conservative wording and more rational and less sensational selection of the excerpts from the film’ (‘Those Exuberant Screen Barkers’ The New York Times July 28 1929, p.5), while Howard T. Lewis insisted that trailer sequences were ‘not always chosen with real appreciation… they do not fairly represent the real character of the play’ (The Motion Picture Industry, New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1933, p. 249). While other opinions were published, they are in a minority: it seems clear that this part of debate around trailer content has been going on for decades, with no end in sight. While I’m not attempting to answer why this recurs so frequently, it is one of the lines of enquiry we hope to pursue in the next phase of our audience research.

‘Trailers can misrepresent a film as their primary aim is promotion/selling’ (#385)

While this respondent understood why a trailer might misrepresent / mislead, many other participant responses were irate about this perceived trend in trailer production. Through the 1930s, there are regular recurrences of this claim that trailers were too loud, over-revelatory, and inclined to misrepresentation of the film. Film Daily opined that the trailer was ‘too elaborately filled with superlatives’ (May 7 1935, p. 8), ‘annoyingly bombastic’ (May 20 1935, p. 8), going so far as to circulate questionnaires asking if ‘trailers show too much of the coming attractions’ (December 2 1936, p. 6).

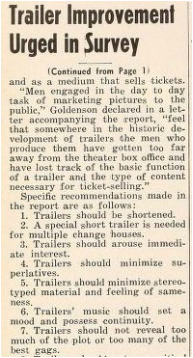

This initial burst of critical trailer talk seems to culminate in a 1948 special exhibitor’s committee. It made 15 recommendations to the trailer industry, which they felt had ‘lost track of the basic function of a trailer’ (‘Trailer Improvement Urged in Survey’, Film Daily March 3 1948, p. 6).

Ryan Gibley has argued that while they were once ‘a sophisticated tease’, modern trailers are ‘annihilating the expectation of excitement, the bliss of ignorance’ (‘Trailer trash’ New Statesmen 13 March 2006, p.42) – while the language of our survey respondents might be softer, there is a partial comparison here: 47 making direct claims that the trailer revealed too much. However, contrary to Gibley’s other claim, there is little evidence from trailer history that points to any sort of Golden Age of trailer sophistication, or that trailers were ever coy about making such plot revelations.

85 years before Gibley’s article (5-9 years after the film trailer was first used in cinema advertising: the debate about what the first trailer was, or when it was released, is a story for a whole other blog) the tone of such industry talk was – initially – kinder. The U.S. Exhibitors’ Trade Review noted that ‘theatres appreciate the artistic and mechanical efficiency’ of the trailer, while a film producer ‘knows that the public is receiving a true and definite conception of what his pictures stand for”.’ (Nov 5 1921, p1597) The idea of a ‘true… conception’ seems far removed from the experience of at least some of our participants, and the wider online debate around trailers regularly returns to the idea of complaints or frustrations over the ‘spoiler’ text.

Positive talk about trailers did not last very long, however. In the early sound era, The New York Times’ Mordaunt Hall demanded trailers of ‘a more judicious fashion, with a conservative wording and more rational and less sensational selection of the excerpts from the film’ (‘Those Exuberant Screen Barkers’ The New York Times July 28 1929, p.5), while Howard T. Lewis insisted that trailer sequences were ‘not always chosen with real appreciation… they do not fairly represent the real character of the play’ (The Motion Picture Industry, New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1933, p. 249). While other opinions were published, they are in a minority: it seems clear that this part of debate around trailer content has been going on for decades, with no end in sight. While I’m not attempting to answer why this recurs so frequently, it is one of the lines of enquiry we hope to pursue in the next phase of our audience research.

‘Trailers can misrepresent a film as their primary aim is promotion/selling’ (#385)

While this respondent understood why a trailer might misrepresent / mislead, many other participant responses were irate about this perceived trend in trailer production. Through the 1930s, there are regular recurrences of this claim that trailers were too loud, over-revelatory, and inclined to misrepresentation of the film. Film Daily opined that the trailer was ‘too elaborately filled with superlatives’ (May 7 1935, p. 8), ‘annoyingly bombastic’ (May 20 1935, p. 8), going so far as to circulate questionnaires asking if ‘trailers show too much of the coming attractions’ (December 2 1936, p. 6).

This initial burst of critical trailer talk seems to culminate in a 1948 special exhibitor’s committee. It made 15 recommendations to the trailer industry, which they felt had ‘lost track of the basic function of a trailer’ (‘Trailer Improvement Urged in Survey’, Film Daily March 3 1948, p. 6).

The recommendations make interesting reading, and we’ve reproduced the list in full here. There are obvious parallels with modern trailer discourse, not least the request that “Trailers not reveal too much of the plot or too many of the best gags” (another area where history and current audience responses overlap). Some of the recommendations may seem irrelevant or frivolous to a modern audience: for example, #11, advising that “Trailers should avoid use of costumes wherever possible”. While it is unclear if this relates to a perception that historical dramas were a ‘hard sell’ (in 1948, at least), the survey as a whole is a fascinating glimpse into the exhibitor perception of how a trailer should work.

“All different aspects of film shown - a great taste” (#488)

Like a trailer, this blog can only offer a taste of almost 100 years of trailer ‘talk’ that was published in the industry and popular press: but it is clear that such ‘talk’ has tended to focus on the negative (I’ll tell you more about the positive another time). The dominant terms have remained the same for much of that period: ‘Misleading’, ‘reveals too much’, ‘best bits’, ‘bombastic’ and ‘too many’ recur through these commentaries, and most of them crop up (to different degrees) in our recent audience survey.

So what does it all mean?

Well, we’re still trying to make sense of that.

There isn’t a simple cause-and-effect model here, but there does seem to be a cumulative discursive effect that builds up across the decades, a calcification of popular discussions of the trailer within particular frames or boundaries. Despite such slings and arrows, the trailer has lived to tell the tale – and is arguably bigger and more influential than at any point in that history – such ‘talk’ appears to have done little to dent that growth, and may actually have encouraged wider engagement with the debate on the value of trailers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed