Despite all the public discourse, and many many compilation lists, and videos, can a movie trailer actually mislead?

This is a question that’s been plaguing me for years, and it’s one that comes up time and again when discussing film promotion and public discourse. Opening her book, Lisa Kernan notes this issue tends to dominate popular dialogue, and indeed the press commentary surrounding the results of the first Watching The Trailer survey focused on this heavily resulting in part in our project to study public discourse becoming part of that discourse.

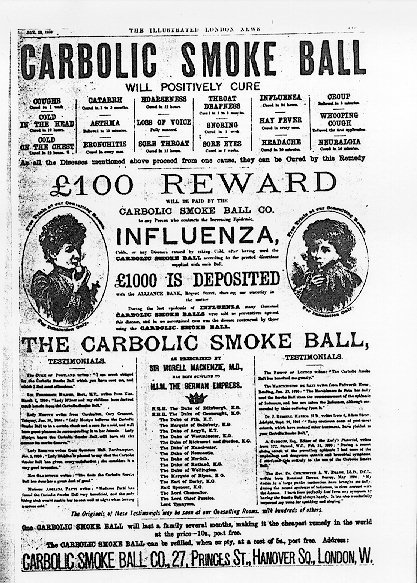

Yet there’s little work in this field beyond public commentary. Trailers are a form of advertising and there are some strict rules surrounding advertising, stemming in part from a English Civil law case for the 1890s; Carlill v Carbolic smoke ball company....

Fast forward to the present day, and within ready memory issues of ‘misleading’ advertising for film promotion are well documented: Sony Pictures for instance was told to pay $1.5million over including critical praise from a reviewer called David Manning. Manning was discovered to be a creation.

Ok so we know for sure that advertising regulation can apply to some elements of the film’ promotion but that case was of posters, what about trailer themselves? Well firstly we need to consider that despite some fairly high profile commentary, there’s no documented case of a trailer being found to mislead within a court of law, and most authorities able to deal with this case typically apply only to trailers on the tv, or pertain about the classification; the suitability of each advert for a particular age group.

(*Authors note: I can’t find any, but welcome anyone who can direct me to one such case).

What there are, however, are a number of complaints, and law suits, which for various reasons are either resolved out of court, or the courts and/or authoritative bodies reject the claims.

In the UK, going to the courts may be possible, but it may seem a bit extreme, you’re more likely to attempt and form of redress by consulting the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) first. This was true of the case in New Zealand of J. Congdon who complained of an explosion that didn’t occur in the film but did in the trailer. The ASA was told by paramount that it’s a “usual and longstanding practice in the film industry” to produce trailers well before the final edit of a movie is submitted. “Thus, despite our best intentions, it is always possible that certain scenes appearing in an advertisement or trailer may not appear in the final version of a film,” and the ASA then took not further action – but Paramount did refund the cinema goers cost of the ticket.

So in this case it was the literal inclusion of an image that didn’t make the final cut. But it’s important to note that this was a trailer that aired on TV, and thus came under the (New Zealand) ASA’s broadcaster remit. (you can read more about this here)

In the UK at least the ASA advised me that (albeit in 2009), if one felt they had seen a misleading trailer at the cinema, my first point of contact was to be the cinema and then the local authority in which the cinema was situated. Why the local authority? Well I believe this stems from the video recordings act (1984), and the various local authorities legislation that (long story short) places the power of authority over the cinema with the local authority. (click here for more info).

Yet there has been at least one high profile case of ‘trailer infidelity’, in which an individual, Sarah Deming attempted to sue for the ‘Drive’ Trailer misleading her into seeing the film. The film she expected to see was more of a Fast and the Furious style of movie… as the Hollywood reporter notes:

"Drive bore very little similarity to a chase, or race action film… having very little driving in the motion picture," the suit continues. "Drive was a motion picture that substantially contained extreme gratuitous defamatory dehumanizing racism directed against members of the Jewish faith, and thereby promoted criminal violence against members of the Jewish faith.

Deming is seeking a refund for her movie ticket, in addition to halting the production of "misleading movie trailers" in the future. The plaintiff intends to turn her individual case into a class action lawsuit, thereby allowing fellow movie-goers an opportunity to share in the settlement reports Detroit's WDIV-TV.

In 2013 however, Deming’s case was dropped after a lengthy process and an appeal. So legally, unless we can find a ruling, we can say that a trailer cannot mislead legally (because shouldn’t all defendants be considered innocent until proven guilty?).

Yet ultimately the lack of case law in this case, doesn't mean that trailers won't be found to mislead in the future. Indeed, we know that trailers can mislead in terms of thematic and character representation, as earlier work in this blog has suggested, you can represent a film in a variety of different ways as Kathleen William’s work on mashup and remade trailers will attest.

The question then remains, can a trailer ever truly represent its movie?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed