Happy New Year Everyone, I want to kick start this year's blog post by thinking back to December 2013... a time a very special trailer was released. I want within this post, to start honing some initial thoughts about the wider theory of the trailer - that of the paratext.

As always, comments are very welcome.

Thanks for joining us in 2016!

Ed

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

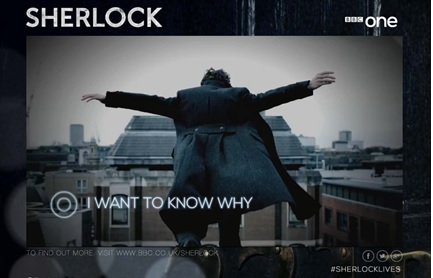

So over the New Year there was a lot of discussion about the new Sherlock episode, which got me thinking about the 'interactive trailer' that aired in 2013. To recap, in December of 2013 to promote the New Years’ episode of Sherlock (The Empty Hearse), the BBC released an ‘interactive trailer’.

This differs from previous incarnations of the trailer that have been conceptualised as short films at a nomenclative and architectural level. Clicking play sets in motion what could be called the horizontal architecture; the trailer plays just like a short film progressing the narrative on the basis of cumulative shorts. Yet this progression has built in interludes that allow for a guided digression.

So interactive is this trailer that linking to the video is proving very difficult. - You can find it here on the host website however.

As always, comments are very welcome.

Thanks for joining us in 2016!

Ed

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So over the New Year there was a lot of discussion about the new Sherlock episode, which got me thinking about the 'interactive trailer' that aired in 2013. To recap, in December of 2013 to promote the New Years’ episode of Sherlock (The Empty Hearse), the BBC released an ‘interactive trailer’.

This differs from previous incarnations of the trailer that have been conceptualised as short films at a nomenclative and architectural level. Clicking play sets in motion what could be called the horizontal architecture; the trailer plays just like a short film progressing the narrative on the basis of cumulative shorts. Yet this progression has built in interludes that allow for a guided digression.

So interactive is this trailer that linking to the video is proving very difficult. - You can find it here on the host website however.

Clicking on these targets (illustrated by the red circle) on the trailer , which themselves are guided with captions, brings up a sub-chapter filled with additional short form content.

In many respects then this trailer has an architecture similar to that of a DVD menu – with a menu screen that runs automatically (in this case the trailer) and with chapter selections that direct you to specific segments (in this case the ‘bonus’ content), these other segments are themselves short films resulting in an interactive narrative that is malleable and divergent from the standard format of the trailer as we know it.

But is this still a ‘trailer’? In departing form the normal format The Sherlock interactive trailer solicits fans’ engagement and actively encourages the click and examine mode of viewing already present in trailer engagement.

So if this is no longer merely a short film, and let us assume for the purposes of this post that its architecture denies this possibility, then do we consider it more of a webpage in its interactive experience. If this is the case how can we understand this form of trailer?

In many respects then this trailer has an architecture similar to that of a DVD menu – with a menu screen that runs automatically (in this case the trailer) and with chapter selections that direct you to specific segments (in this case the ‘bonus’ content), these other segments are themselves short films resulting in an interactive narrative that is malleable and divergent from the standard format of the trailer as we know it.

But is this still a ‘trailer’? In departing form the normal format The Sherlock interactive trailer solicits fans’ engagement and actively encourages the click and examine mode of viewing already present in trailer engagement.

So if this is no longer merely a short film, and let us assume for the purposes of this post that its architecture denies this possibility, then do we consider it more of a webpage in its interactive experience. If this is the case how can we understand this form of trailer?

Trailers have, for the most part been considered as paratexts, those objects that condition our engagement with a central object. Indeed, I would suggest that this concept of the trailer not being the central object, is one of the reasons there are so few scholars in the area. While this trailer retains its promotional qualities - referencing the television event that had (in December 2013) yet to be released, this trailer solicits engagement at an architectural level and can be said to form a stand alone experience - bringing this trailer back into the realms of text, rather than paratext.

While this trailer-text is still conditioning our engagement with the television show, through both content and architecture that references the detective genre, the act of soliciting engagement and holding it's own hidden content belies the very understanding of the paratext. In short this trailer, through soliciting attention becomes the focus, rather than just an addition to something bigger.

To be fair, when Genette penned his work on paratexts, he was focusing on physical books, including within his work the typography, margins, and titles, but also included interviews with authors, critical reviews, book covers and posters, etc. The point for Genette, appears to be one of audience/consumer goals and intended purpose of these ‘lesser' objects, as consumers we do not pay for the promotional materials, but rather the thing to which it refers which is nearly always sold, this act of referring could be said to create a hierarchy in which one object has more value than another.

I want to suggest, however briefly, that this particular trailer illustrates the problems with the term ‘paratext’ in relation to all trailers. In soliciting our attention within the architecture, the trailer becomes the focus and object or text, and in existing in advance of the TV show, acts metonymically as the show – how often do we see a poster or trailer and decide that the film referenced isn’t for us? In such instances the paratext is standing in for the text becoming the text for those of us who are not interested. Even if we engage with the trailer knowing we will see the object referenced, it becomes stored within our wider textual experience of the show, film, franchise, genre, or body of work of a specific creative professional. In short, surely the act of calling attention to oneself for whatever purpose is the act of creating a text? Here, I want to stop, in part because these ideas need to be fleshed out more, and require the theoretical rigour that belongs in a paper rather than a blog post, but I do want to posit the notion that

in the case of promotional paratexts, these tend to deny their existence as such through drawing attention however briefly, to themselves.

Trailers have, for the most part been considered as paratexts, those objects that condition our engagement with a central object. Indeed, I would suggest that this concept of the trailer not being the central object, is one of the reasons there are so few scholars in the area. While this trailer retains its promotional qualities - referencing the television event that had (in December 2013) yet to be released, this trailer solicits engagement at an architectural level and can be said to form a stand alone experience - bringing this trailer back into the realms of text, rather than paratext.

While this trailer-text is still conditioning our engagement with the television show, through both content and architecture that references the detective genre, the act of soliciting engagement and holding it's own hidden content belies the very understanding of the paratext. In short this trailer, through soliciting attention becomes the focus, rather than just an addition to something bigger.

To be fair, when Genette penned his work on paratexts, he was focusing on physical books, including within his work the typography, margins, and titles, but also included interviews with authors, critical reviews, book covers and posters, etc. The point for Genette, appears to be one of audience/consumer goals and intended purpose of these ‘lesser' objects, as consumers we do not pay for the promotional materials, but rather the thing to which it refers which is nearly always sold, this act of referring could be said to create a hierarchy in which one object has more value than another.

I want to suggest, however briefly, that this particular trailer illustrates the problems with the term ‘paratext’ in relation to all trailers. In soliciting our attention within the architecture, the trailer becomes the focus and object or text, and in existing in advance of the TV show, acts metonymically as the show – how often do we see a poster or trailer and decide that the film referenced isn’t for us? In such instances the paratext is standing in for the text becoming the text for those of us who are not interested. Even if we engage with the trailer knowing we will see the object referenced, it becomes stored within our wider textual experience of the show, film, franchise, genre, or body of work of a specific creative professional. In short, surely the act of calling attention to oneself for whatever purpose is the act of creating a text? Here, I want to stop, in part because these ideas need to be fleshed out more, and require the theoretical rigour that belongs in a paper rather than a blog post, but I do want to posit the notion that

in the case of promotional paratexts, these tend to deny their existence as such through drawing attention however briefly, to themselves.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed